|

When electronic musicians talk tech, we usually focus on which gadgets are the coolest. We swap sound-design ideas and recording techniques and moan about lousy tech support. But somehow, no matter how many opinions we offer about what to buy, we rarely discuss how to assemble the system once we buy it. That's understandable, but it's a big oversight. Systems design in general, and rack design in particular, are crucial in putting together a quality music production and performance environment. And if your stage or studio environment stinks, you have to work much harder to produce a quality product. When you take your act to the stage, a poorly designed system can lead to catastrophe. Technical tragedies can range from unacceptable noise and system failure to flaming equipment racks and electrocution. At various points in my career, I experienced all of these and more. (I once got blown some seven feet across an outdoor stage because of a poorly grounded system. I crawled back and finished the song on my knees!) But you don't have to learn these lessons the hard way if you rack-mount your electronic brain the way the pros do. To help you rack your brain, I consulted two top gear gurus. Nashville-based Ernie Bartschi is a refugee from New York City, where he was the rehearsal/equipment manager for SIR. Today, Bartschi's ECB Sound creates custom touring and studio systems, with a special fondness for guitar systems. Programmer, engineer, and producer Bryan Bell is the president of SynthBank, a high-tech music-consulting firm. Bells clients include Branford Marsalis, Santana, Neil Young, and INXS, but he is best known for his association with Herbie Hancock. What You Want The size of the venues affects the mode of transportation, which in turn helps determine the type, size, and weight of your racks. Sometimes you need just a few synths for a quick gig, especially if the synths have onboard effects. Other times, you might need a full-blown package, with an integrated stage-monitor system.

Bartschi notes that your musical style is important: a country guitar-picker might not need the same extensive effects and complex signal routing required by a metal fretmaster. He also inquires about your musical responsibilities. Are you the only guitar player? Do you have to play rhythm and lead, and also trigger sequences? Bell points out that touring players have another consideration: practicing and composing in the hotel room. If you're on a club tour by bus or truck, you might be able to create a small rack for the hotel room that fits into the larger performance rack system at the gig. But if you're doing stadium dates on a large concert tour, the crew needs to pack your rig into a semi-truck or airplane and head for the next city as soon as you finish a show. In this scenario, there's no way you can use the same rack onstage and in the hotel room or tour bus. Most musicians also must integrate their rigs into a studio. If you do dates at a pro studio, you usually rely on the studio's board and effects processors. But unless you are sure of the studio's available equipment, you'll want your own sound sources. If you have a home studio, you probably use almost all of your live system there, possibly including a computer. Many musicians combine touring, pro recording, and home use, so flexibility is important. |

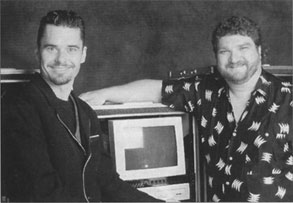

"Most people want everything in one rack-the mixer, preamps, processing, and synths," says Bartschi. "I have no problem with that, to a point. It's better to leave the power amps and such at your home studio and just take mixer, preamps, synths, and effects to the gig. If you're touring with your own monitor system, you usually put the power amps in a separate rack to minimize noise and heat. Amp racks should be kept small because they tend to be heavy." With computers, Bartschi recommends keeping the monitor screen separated, in its own case, padded with 2-inch foam. Make sure the case has a rear door for cables and ventilation. "You can set the monitor on top of your main rack so it's visible," he notes, "while the rest of the computer hooks up in the main rack. Just keep it away from speakers and power amps." How many people will handle your rack system? If you're working with a huge tour, for instance, you'll have a professional crew and a forklift, so it's a lot easier to use large racks. Such a system can be largely prewired, perhaps with multipin connectors, which makes it the easiest to set up. "Even then," argues Ernie Bartschi, "keep it as relatively small as possible, so it's easy to move. Your crew will hate you if they have to wrangle a 32-space rack. You're better off with smaller racks. However, if all your components have to be in one rack, get an extra-deep rack, so some things are in front and some in back." Fro many Bartschi clients, a 16-space rack is the maximum. E Pluribus Unum For example, if you were a hot session player in Los Angeles or New York in the I 970s, and your rack system could be handled in a 12-foot van with a lift gate, a service was hired to cart your gear to the venue. Today, you are usually expected to bring your own gear via private car or taxicab. So the minimum physical criteria for artists in this situation are the entrance to a car and the weight the artist can comfortably carry. If you travel by van or truck, you might just have to load the racks onto a small hand truck and slip them through a standard, 29-inch building doorway. "But," points out Bell, "don't forget, you may have to get your rig upstairs, whether at the gig or upon returning home. Then, size and weight become huge factors." In Bell's book, even four synths and samplers can be too heavy to carry, especially if they have hard drives. A sampler, DAT machine, and modular digital multitrack in one rack is also too much. To deal with these realities, Bell designs systems consisting of several small racks, each of which is a functional block. For instance, the sound modules and MIDI processing can be put in one instrument rack. For an elaborate system, this might include a drawer for a drum machine or special MIDI device. It's also a good idea to include direct boxes within the instrument rack. That way, if you don't need to use your mixer, you can bypass it and get top-quality sound. This system offers maximum flexibility. The synths' audio signals usually don't need to be mixed within their rack, as you would route them to the main PA. or studio console. For live work, you can use the synths' onboard effects, and in the studio, you call use the studio's effects. Thus, the instrument block is autonomous.  INXS drummer John Ferriss (left) with programmer, engineer, and producer Bryan Bell. Bell's other clients include Branford Marsalis, Santana, Neil Young, and Herbie Hancock. |

EM Senior Editor Steve O has grown old and gray from designing too many rack systems, years of roadwork, and nasty editing deadlines. |

|